My favorite part of doing history is to follow a trail of evidence that reveals a compelling story that was forgotten or suppressed for hundreds of years. This article is outside my usual focus of Concord, but it’s an outstanding example of this kind of detective work by Fara Dabhoiwala, published in the London Review of Books in November 2024.

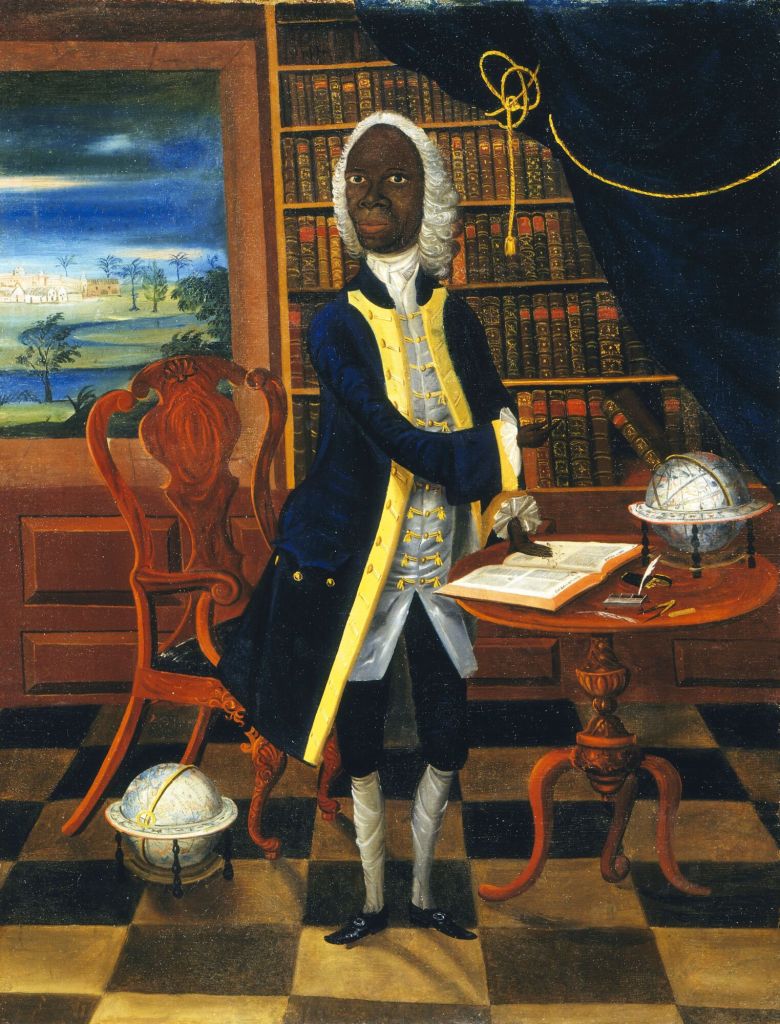

An obscure 18th-Century portrait turned up in England in a 1928 estate sale. It had once belonged to Edward Long (1734–1813), the owner of a sugar plantation in Jamaica, and had passed through generations of his family. The man in the portrait was Francis Williams (ca. 1690–1762), a Black Jamaican man whom Long had written about in a history of Jamaica that he published in 1774.

Dabhoiwala, a history professor at Princeton, studied Long’s text on Williams and discovered that much of it is false. Long wrote it after Williams’s death, and he blatantly distorted or omitted the considerable achievements of his subject.

Williams was born into slavery in Jamaica, but when he was a child he and his parents were emancipated. They prospered as merchants, and in time became landowners who enslaved other Black people to work on their land. They sent Francis to study at Cambridge in England. He attended meetings of The Royal Society, and was even nominated for membership. (They rejected him because he was Black.)

Thanks to his conversations with Royal Society scientists—among them Isaac Newton and Edmond Halley—Williams became interested in Halley’s Comet, and Newton’s dauntingly complex calculations to predict when it would next be visible from Earth. Those calculations appear on page 521 of Newton’s Principia, which is the page Williams’s left hand rests upon in the portrait. Through the window behind Williams we can see Halley’s Comet in the night sky.

Fara Dabhoiwala concludes that the inclusion of Halley’s Comet and Newton’s Principia in the picture signify that Williams had studied Newton’s work and used it to accurately calculate the time of the comet’s return.

Dabhoiwala also debunks the notion that that the picture was intended as a caricature, noting that figures with large heads and small legs and feet were characteristic of some portraits by William Williams (1727–1791), an English-born artist who traveled to Jamaica at the time this portrait is believed to have been painted.

Francis Williams rose from enslavement to become a wealthy landowner admired by his contemporaries for his scientific and literary accomplishments. He was ignored for centuries by historians unwilling to honor the deeds of a Black man. Dabhoiwala dug deep to find the primary sources that bring Williams’s story back into the spotlight where it belongs.

Here’s the link to the full article in the London Review of Books:

https://www.lrb.co.uk/the-paper/v46/n22/fara-dabhoiwala/a-man-of-parts-and-learning . It’s a longish article (8000+ words), but well worth the effort to read.

Image: Francis Williams, Scholar of Jamaica, attributed to William Willams, ca. 1760. Source: Victoria and Albert Museum, London