Isabel Bliss hurried her three children, aged four through seven, off to bed on the night of March 20, 1775. The two men who had come to her door looked like local farmers seeking counsel from her husband, lawyer Daniel Bliss. They wore the homespun coats of plain country folk, but the muskets they carried told a different story.

As the men huddled with Daniel in the parlor, talking in whispers, Isabel was startled by another knock at the door. She opened it cautiously and was relieved to see the familiar face of a neighbor. The woman was out of breath, and tears stained her cheeks. She begged Isabel to forgive her, because she had given the two strangers directions to the Bliss home without knowing who they were.

Concord was a small community in 1775, with a population around 1,500, and the Bliss family lived right in the middle of it, just a few steps from the milldam. As the strangers approached their highly visible home, local patriots recognized them as officers of the occupying British army, disguised as civilians to gather intelligence for their commander, General Thomas Gage.

Squire Daniel Bliss was a prominent and respected member of the community, but just three months earlier he had exposed his loyalist sympathies at the Middlesex County Convention. “The colonies are England’s dependent children,” he declared. “Cut off from Britain, they will perish.” When army spies were seen going into his house, it wasn’t hard to figure out that he was giving them information about the caches of arms and ammunition concealed around Concord.

Now the woman who had given them directions stood in the Blisses’ front hall, sobbing that she had been threatened with tar and feathers for her mistake. Worse, she said, Concord patriots had given her a message for Squire Bliss: If he was still in town the next morning, he would pay for his treachery with his life.

The two spies—Captain John Brown and Ensign Henry De Berniere—at once proposed to escort Bliss out of town, defending him with their muskets if necessary. They left under cover of darkness via a back road that took them to Lexington and on to the safety of the British garrison in Boston.

The terrified Bliss had left Isabel and their three children behind in Concord. His neighbors’ rage had been directed at him, not them, but he knew they wouldn’t be safe for long. He sent word to his brother Samuel (also a loyalist), asking him to bring Isabel and the children to join him, and they soon fled to Canada.

Squire Daniel Bliss and his family settled in Quebec, where he served in the British army during the American Revolution and rose to the rank of colonel. In 1780 he and Isabel welcomed a fourth child, Hannah. After the war, he and his family moved to Fredericton, New Brunswick, where he resumed his law career. He prospered and went on to become the head of the New Brunswick Bar, and the Chief Justice of the Court of Common Pleas. Bliss lived in New Brunswick until his death in 1806.

Text excerpted from “Daniel Bliss and John Jack: Loyalty’s Cost, Freedom’s Price,” published in the Fall 2024 issue of Discover Concord Magazine. Click here to read the full article.

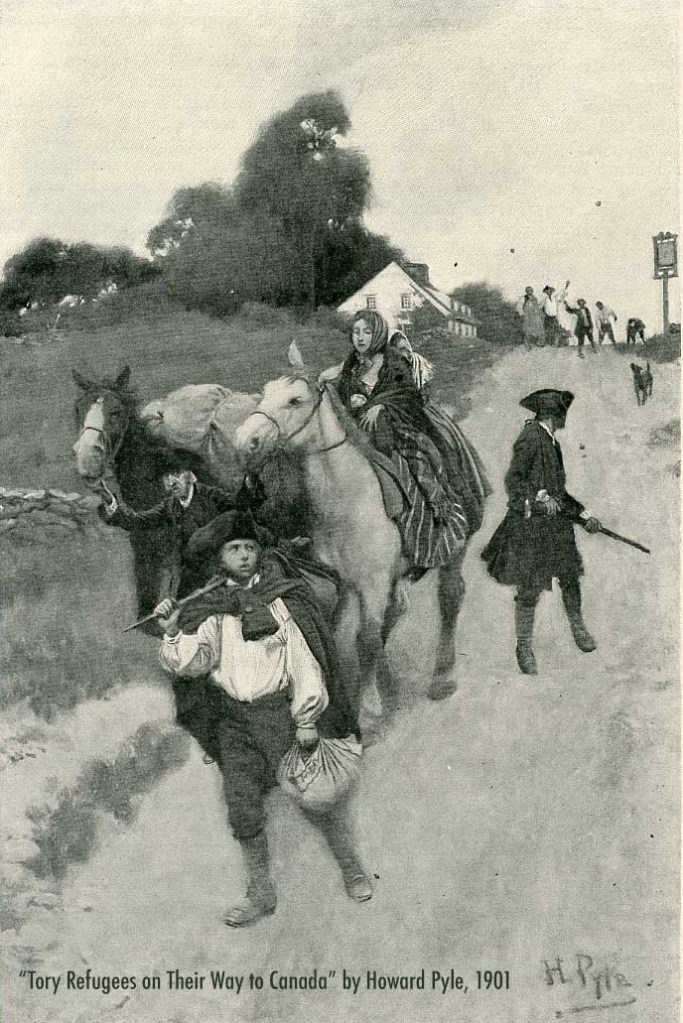

Image: “Tory Refugees on Their Way to Canada” by Howard Pyle, 1901 (public domain)